The mobile age is upon us and the use of strategic alliances amongst the players within the mobile ecosystem is rapidly becoming a business imperative (Overby, 2005). This is due to the fact that the mobile industry, like other technically volatile end emergent industries (Porter 1990, Doz and Hamel 1998), is becoming increasingly impacted by the effects of globalization, the spread of inter-linked heterogeneous technology, and global acceptance of harmonized standards, all of which are blurring the boundaries of previously autonomous, unrelated, industries and firms that serve them (Contractor & Lorange 2002; Gomes-Casseres 1996; Bergquist & Betwee 1995). The cumulative effect of these trends is making it increasingly evident that the mobile ecosystem players—brands, content owners, marketing agencies, media & retail companies, enterprises, application providers, and even network providers—wishing to launch mobile and mobile-enhanced initiatives (Becker 2005a) will find it prohibitively difficult to fully internalize (while not exposing themselves to unnecessary risks) the necessary systems, processes, technology, skills, know-how, marketing, and managerial expertise needed to develop and sustain a competitive advantage in the markets they serve (Dacin et al. 1997, Glaister & Buckley 1996; Akio 2004; Gates 1993; Taysen 2004; Porter 1990). Firms interested in offering compelling mobile and mobile-enhanced services are turning to strategic alliances with complementary firms, and in some cases competitors, to reduce their risk, gain access to technology, know-how, new markets (local, national, and global), marketing expertise, and products and services in order to excel in today’s fast-paced technically and socially complex mobile market. This article discusses the nature of the mobile ecosystem and the use of strategic alliances by the players within it. It identifies key strategic alliance elements and concludes with a framework that practicing managers may consider when formulating and managing their strategic alliances.

Today, mobile voice and data services are being used by nearly 20% of the world’s population, 65~100% of the population in industrialized nations. Mobile services and mobile-enhanced services are ubiquitous and used to for personal communication, social networking, traditional media, data requests and dissemination, content sales and delivery, artistic expression, business, healthcare, gaming, fitness, and direct 1 to 1 marketing, to name just a few of the applicable areas. Mobile terminals, the devices that enable access and interaction to and with these services, come in a wide range of shapes and sizes and can be found in some interesting places, including on belts, lanyards, kid’s shoes and backpacks, pet collars, in pockets, watches, purses, art exhibits, cars, elevators, parking meters, they can even be found on the backs of pigeons where they’re being used for air quality monitoring. Mature mobile services like voice, text messaging, mobile email, wallpaper, games, and ringtones sales have become immensely popular, but these services simply form the foundation for the next generation services to come. Additional services are gaining mass-market awareness like push-to-talk, picture messaging, mobile instant messaging, mobisode and mobile TV viewing, full-length music downloads, and 3d and interactive gaming. Other services, including permission-based location-aware applications, remote salesforce and field service management, as well as mobile enhanced interactive customer relationship management are not far off, as are the availability of more elaborate services that will take advantage of the convergence of both long and short range wireless offerings, including 3G and 4G networks, WiFi, Bluetooth, RFID, near field communications, etc. All these services are powered by the interaction between professionally and technical diverse players within the mobile ecosystem.

Strategic Alliances and the Mobile Ecosystem

Given the wide range of converging and heterogeneous technologies and practices that are powering mobile initiatives within the mobile ecosystem, it is no wonder that the use of the strategic alliance business vehicle is rising. Even though most alliances fail, typically 50%~60% of strategic alliances fail (Hosskisson 1999), studies have shown that across all business sectors strategic alliances usage increased by over 25% in the 1990s (Contractor & Lorange 2002), and the mobile industry has followed suit. Taysen (2004), in his recent study, informs us that strategic alliance use in the mobile space is growing, with the average firm in the mobile space by 2006~2007 estimated to be engaged in 31 strategic alliances, which is up from 16 alliances in 2001. Again, the increased usage of the strategic alliance vehicle is due to the fact that firms are finding it more and more advantageous to collaborate when reaching out to the market.

According to Becker (2005b) the mobile ecosystem consists of four interlinking spheres, or micro-markets: Product & Services, Media & Retail, Applications, and Connections. The players within each sphere are domain experts specializing in discrete areas like creative design, product positioning, consumer interaction, content creation and publication, technology development, network management, and regulation development, etc. Product & Services companies manage the conception, development, release of content, products, and service to be sold to the markets. Media and retail players provide channels for promotion, distribution, and point of sale commerce. Applications providers develop the hardware and software solutions that enable mobile interactivity, and Connection players are the backbone to the mobile industry providing the infrastructure and support for the fundamental business models powering wireless services. Mike Short, the Chairman, Mobile Data Association, recognizes the need for partnerships in the mobile space and how they will drive the industry by noting that:

“if Content is King, the Carriage is surely Queen- and Mobile Content a Royal Wedding!... This truly requires partnerships to blend the best of all Content on the relatively small screen of mobile, whilst also recognizing that historically it is the fourth screen coming in time after film, TV, and PC screens, but of course with the true attribute of mobility, interactivity, global reach, and personalization. These attributes could one day make the mobile the first screen if the partnerships work well…the need for mobile partnerships with specialists who understand how the various Messaging solutions are rapidly evolving, based on new Mobile and Internet combinations. While the key Messaging focus areas of Push to Talk, Mobile email and Instant messaging are all stressed, it is only the specialists who can match this to actual network capability, handset adoption and country penetration (this is far from uniform internationally), handset capability and real user needs…among these trends, the market fog needs to be cleared with real partners, able to show the way forward towards real solutions and growth.” (Netsize Guide 2006, p8).

Take, for example, a technically straightforward mobile initiative like the American Idol text messaging voting application, which is arguably has been the most effective and prominent mobile marketing initiative to date in the United States. A program like this requires the seamless interaction of many firms within the mobile ecosystem. To make the American Idol mobile initiative happen, the American Idol Brand Managers partner with players for each sphere of the mobile ecosystem. Within the Product and Services sphere, they work with their marketing agency and content partners to conceive of the program details, and they’ll work with their media and retail partners to promote the program. The Brand Manager will also work with an Application provider to gain access to the mobile voting application, who in turn works with a Connection player for messaging delivery and related network elements. What appears to be a rather straight forward initiative, mobile enhancing a TV program with text message voting, is actually quite complex and seamless interaction and alignment between multiple companies across many micro-markets.

Strategic Alliances Defined

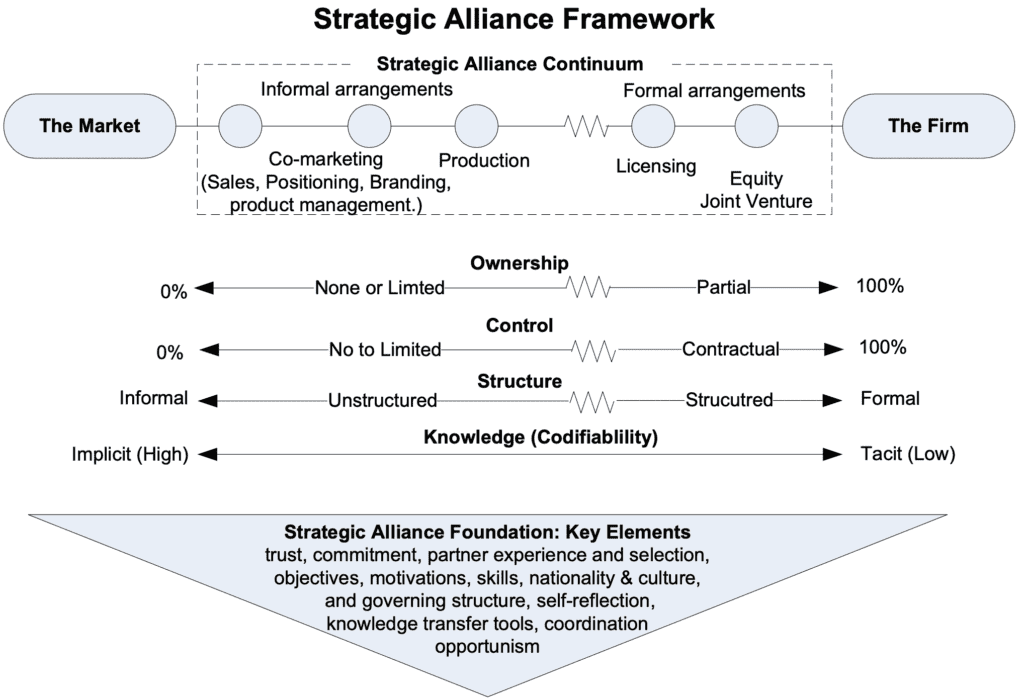

A strategic alliance, or partnership as it is often referred to, is a business relationship that exists between two or more firms, one that materially contributes to the firm’s competitive position (i.e. is strategic) and that takes on a governance form between two polar opposites, the open market and the hierarchy of the firm (Kogut 1988, Williamson 1991; Ireland et al. 2002; Gilroy 1993; Porter 1990). Prior to 1988 strategic alliances were not widely used and the most common form of the strategic alliance was a joint venture, an inter-firm relationship characterized by firms joining known resources and addressing known risks in order to address specific opportunities peripheral to the firm’s core strategy (Kogut 1988, Doz & Hamel 1998). However, since then the notion of the strategic alliances has matured greatly, today the strategic alliances exist in a continuum between the open market and firm. Gomes-Casseres (1996) notes that strategic “alliances blur the boundaries of firms, making it hard to discern where one firm ends and where another--or the market—begins… an alliance is any governance structure involving an incomplete contract between separate firms an in which each partner has limited control… a contract is termed incomplete when, despite the fine print, it does not specify fully what each party must do under every conceivable circumstance” (p34)

What makes strategic alliances unique is that they are not as formal as the firm in terms of ownership, control, and structure or as informal as the market where no ownership, control, or structure is afforded to the firm. Another element within the strategic alliance framework is knowledge management which exists on a continuum between implicit knowledge, that which can be bought opening in the market, and tacit knowledge, or that which is socially complex and experience-based and only accessible through the interaction with a partner or built internally over time within the firm.

The above elements alone do not make the strategic alliance relationship between firms unique. In addition to these elements, there are a host of other factors that act as stabilizers and de-stabilizers to the alliance relationship between firms, including partner experience and selection, the objectives of each partner, partner motivations, skills, individual firm and local governing and economic structures, culture, heritage and more. All these elements significantly affect the nature and success of strategic alliance as depicted in the illustration below.

Figure 1: Strategic Alliance Framework

This framework, by identifying the critical elements that should be considered when forming a strategic alliance, can help practicing managers within the mobile space improve the success of their alliances. Hosskisson (1999) reports that there is a high rate of failure of the general strategic alliances, but research also shows us that the firms that proactively manage their strategic alliances achieve higher than normal returns, specifically it has been shown that “strategic alliances have consistently provided a return on investment of nearly 17 percent among the top two thousand companies in the world for nearly ten years…[and that] successful alliances builders expect about 35% of their revenue to come from alliances” (Harbison & Pekar 1998). The builders of strategic alliances learn early that, while they do need to be concerned about the possibility of partner opportunism (and minimize it if at all possible), mutual trust, commitment, and cooperation forged over time will lead to the establishment of lasting foundations and strategic alliance success (Williamson 1985, Ireland 2002). When handled properly factors like trust and commitment can mitigate challenges in alliance formation and management. They can also contribute to the generation of social capital between the aligning firms. Social capital may be considered a resource since it is rare, valuable and difficult to imitate, and if managed properly the nurtured social capital may become a core competency of the firm and contribute to its competitive advantage. "Partnerships that move beyond form and structure--those that demand deeper changes, in principles and behavior--will recognize the interdependence of multiple parties and replace control with cooperation and collaboration… In an age of limited and diminishing resources, partnerships offer expanded capabilities, allowing organizations to do more with less or do something entirely different than their existing resources base permits. Increasingly, professional people have found hierarchical structures too inefficient to achieve their goals. ” (Bergquist & Betwee 1995:PG9, 11).

The mobile ecosystem is a technologically and professionally diverse web of micro-markets and companies providing a complex mix of interlinking branded products and services, all seamlessly coming together to power mobile and mobile-enhanced initiatives. As the trends of globalization, standards and regulatory harmonization and convergence continue the need for strategic inter-firm or alliance, relationships will only increase. Successful alliances require a firm’s management to apply flexible, patience, forbearance, time and most importantly have a desire to learn and improve.

This paper is a synthesis of a larger work by Becker on strategic alliance theory and practice. Contact the Michael Becker at michael.becker@iloopmobile.com if interested in receiving a copy of the complete piece.

References

Akio, T. (2004). The Logic of Strategic Alliances. Ritsumeikan Intentional Affairs, 25, 79~95.

Becker, M. (2005a, 6/Dec). Effectiveness of Mobile Channel Additions and A Conceptual Model Detailing the Interaction of Influential Variables. Retrieved 4/13/06, from http://mmaglobal.com/modules/wfsection/article.php?articleid=131.

Becker, M. (2005b). Unfolding of the Mobile Marketing Ecosystem: A Growing Strategic Network. Retrieved 4/13/06, from <http://mmaglobal.com/modules/wfsection/print.php?articleid=74>.

Bergquist, W., & Betwee, J., Meuel. (1995). Building Strategic Relationships. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Contractor, F., & Lorange, P. (2002, 06/03/25). The Growth of Alliances in the Knowledge-Based Economy. In F. Contractor & P. Lorange (Eds.), Cooperative Strategies and Alliances (pp. 3-22). London: Pergamon.

Dacin, M. T., Hitt, M., & Levitas, E. (1997). Selecting partners for successful international alliances: Examination of U.S. and Korea firms. Journal of World Business, 32, 3-16.

Doz, Y., & Hamel, G. (1998). Alliance Advantage. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Gates, S. (1993). Strategic Alliances: Guidelines for Successful Management. Ottawa: The Conference Board.

Gilroy, B. M. (1993). Networking in Multinational Enterprises. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press.

Glaister, K., & Buckley, P. (1996, May). Strategic Motives for International Alliance Formation. Journal of Management.

Gomes-Casseres, B. (1996, 06/03/29). The Alliance Revolution. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Hoskisson, R., Hitt, M., & Wan, W. (1999). Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum. Journal of Management, 25(3), 417-456.

Ireland, D., Hitt, M., & Vaidyanath, D. (2002). Alliance Management as a Source of Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 28(3), 413-446.

Kogut, B. (1988, 23/July). Joint Ventures: Theoretical And Empirical Perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 9, 319-332.

Overby, M. L. (2005). Organizing Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Case of Mobile Telecommunications.

Porter, M. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. New York: The Free Press.

Short, M. (2006). One of us must know The Netsize Guide (2006 Edition). Retrieved 21/02/06, from Netsize: http://www.netsize.com/index.aspx?id=5&sid=1.

Taysen, N. v. (2004). Commitment as Performance Factor of New Venture Alliances in Mobile Business [Electronic version].

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. The Free Press.

Williamson, O. E. (1991, June). Comparative Economic Organization: The Analysis of Discrete Structural Alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 269~296.

No Comments.