Zeynep Tufekci, an information science professor, wrote a powerful and timely piece in the New York Times this week, Think You’re Discreet Online? Think Again (Tufekci, 2019). She wrote about data inference, a topic I think we all need to understand since what it means is that we are all being measured, scored, and accounted for.

A challenge with the industry practice of data inference is that the vast majority of the population has no idea that it is happening and how it works, and more importantly what to do about it.

Data inference

Data inference refers to the use of data and computer algorithms to infer insights, as well as resolve identities, about individuals or groups of individuals.

There are other terms in use for data inference.

In marketing, for example, we'll often use terms like predictive analytics, recommendation engine, consumer scoring, or intent and destination marketing (see how Waze is leveraging data for destination marketing) to refer to the concept data inference.

According to Pam Dixon (2014) at the World Privacy Forum, the goal of data inference, or a consumer scoring as she puts it in her 2014 report The Scoring of America: How Secret Consumer Scores Threaten Your Privacy and Your Future, is to predict or derive an individual's or groups of individuals' characteristics, habits, behaviors, or predilections.

Common predictions being made about individuals or groups include,

- Creditworthiness (i.e. their credit score)

- Likelihood to buy a good or service

- Potential to churn from a service

- Potential to participate in one or other social circles

- Likelihood to engage in fraud or some other criminal activity

- Wealth

- Lifetime value

- Movements

- Disease propensity

- Political affiliation

- Propensity to vote in a certain way

- Religious preference

- Sexual preference

- Worthiness of being targeted

- and more

According to experts, there are hundreds if not thousands of inferences made about each and every one of us, every day. For example, data inferences are used to determine the type of advertising or content someone might see, if they can get a loan or not, deserves a price discount or not, are a candidate for medical treatment or not, are a worthy candidate of a job or not, etc.

We have no or little chance to gain access to the data being used to make inferences about us (even with GDPR and CCPA), let alone have the opportunity to influence the algorithms.

The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

There is nothing inherently good, bad, or ugly about all this scoring.

The commercial or moral interpretation of the results that come from decisions being made based on the derived insights is in the eye of the beholder.

The Good

Tremendous individual, private and public good comes for the effective use of data and the resulting inferences. For example,

- Public good, In 2013 Cisco predicted that $19 Trillion of net economic value would be generated worldwide by 2023 from the productive use of data (Bradley et al., 2013).

- Private good, Proctor and Gamble, the world's second-largest advertiser has collected over 1 billion customer identities in its data management platform and uses them to reduce media waste, increase media reach, and get closer to the consumer; to be more relevant and effective with its one-to-one marketing (Pritchard, 2019).

- Individual good, individuals are using data inference for all kinds of quantified self efforts, including health tracking, financial monitoring, social engagement, management of vulnerable family members, and so much more.

The bad

While there is much good to be had from data inferences, there can also be bad, especially when inferences are based on bad data or racially, gender or otherwise biased algorithms, or when data has been breached. These inferences and misuses of data may lead to poor or harmful decisions and crime.

Due to bad data and biased algorithms people have missed out on commercial offers, job opportunities, have been severely injured, and even put in jail. All because the data was not clean, misinterpreted, or misrepresented.

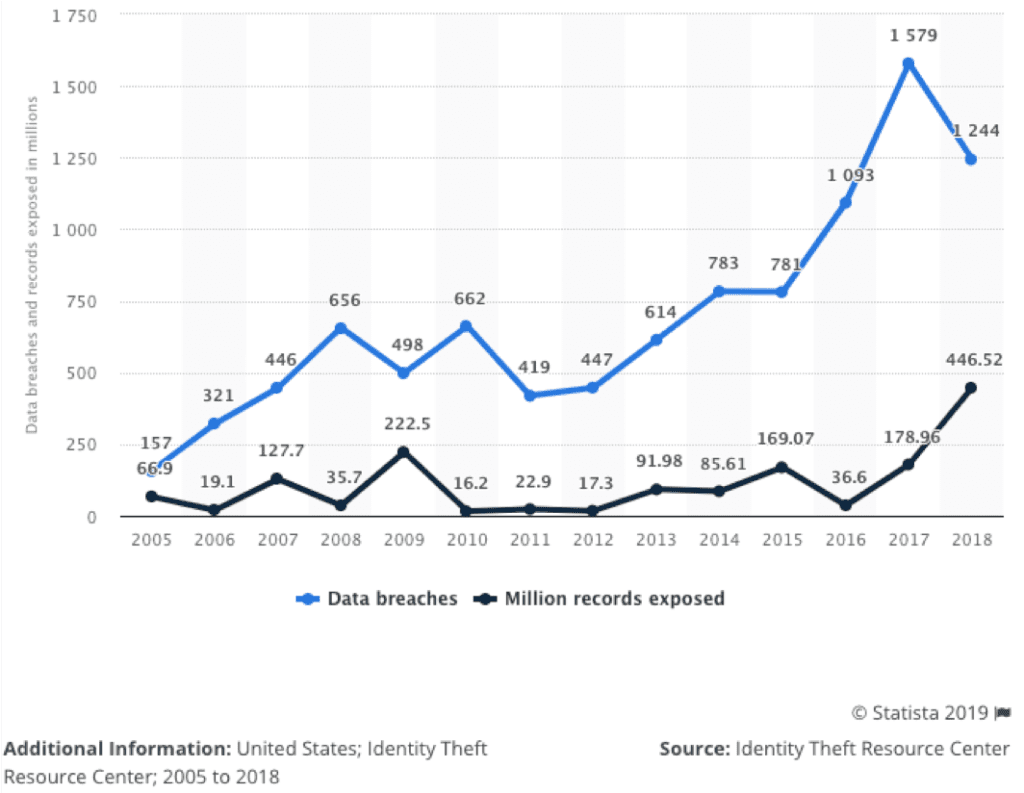

Moreover, when our data has been leaked or breached, according to Javelin Research (2017), we're 11 times for likely to be a victim of identity theft. This is a sobering thought when you consider the magnitude of the data breaches that have occurred since 2005.

The Ugly

Data inferences are happening all around us, all the time.

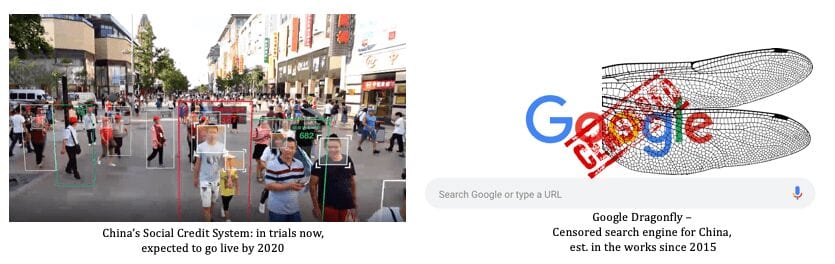

China, however, has taken data inferring to a whole new level, having recently launched a nationwide social scoring system that is expected to be fully functional by 2020. Every Chinese citizen is being scored using public and private data. Their individual score will determine where they can live, what job they can have, if they can buy a train or plane ticket, etc.

These Chinese practices are reminiscent of fiction becoming a reality. Remember the 2016 Black Mirror episode Nosedive? Well, it's here. It is a reality, not fiction anymore.

And, Its All Just Getting Started

More and more inferences are being made on every one of us, every day, as more and more data are being collected.

IDC predicts that by 2025 the global datashpere will grow to 163 zettabytes (that is trillion gigabytes) and "an average connected person anywhere in the world will interact with connected devices nearly 4,800 times per day — basically one interaction every 18 seconds" (Reinsel et al., 2017).

To put 163 zettabytes into prospective it is roughly equivalent to stacking 40 million DVDs which would reach the moon and back 100 million times (Bajaj, 2017).

What this means is that, as we navigate our lives, more and more of our data will be collected and analyzed and used to predict or derive our characteristics, habits, and behaviors.

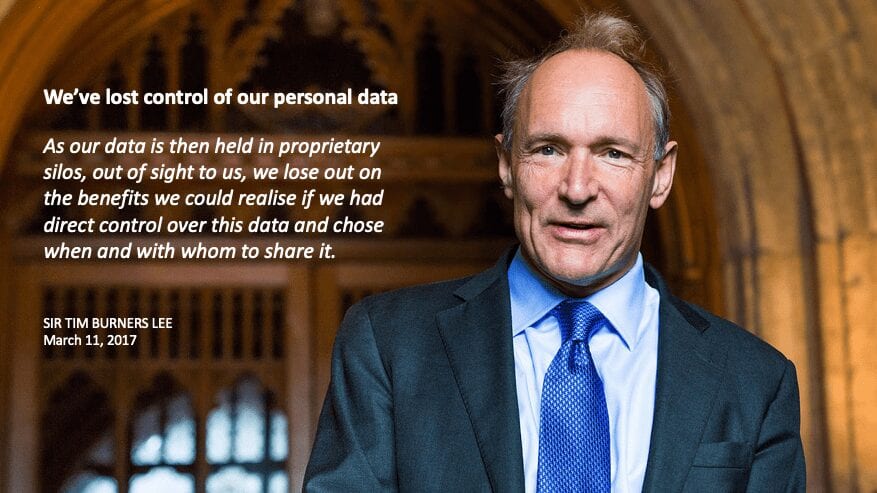

We've lost control of our data

People have little to no control over their identity or personal data today, let alone the ability to control how they're being scored or labeled.

Tufekci offers a few recommendations on what we should be doing about this. She suggests that we need to

- Design phones and other devices to be more privacy-protected

- Establish government regulation of the collection and flow of data

- Start passing laws that directly regulate the use of computational inference: What will we allow to be inferred, and under what conditions, and subject to what kinds of accountability, disclosure, controls and penalties for misuse?

I agree with her recommendations and in many ways leading industry players agree with her too. For example, Apple recognizes that privacy is a luxury good and has built privacy into the core of its product offerings and market positioning.

"Today that trade has exploded into a data industrial complex. Our own information, from the every day to the deeply personal, is being weaponized against us with military efficiency," Cook said. "We shouldn't sugarcoat the consequences. This is surveillance," Cook said. "And these stockpiles of personal data serve only to enrich the companies that collect them.”

Tim Cook, Apple, CEO, October 24, 2018

And, just this week, Brave announced that it will pay users a portion of the revenues Brave generates from the advertising they see.

In addition, new regulations like GDPR in Europe and the California Consumer Privacy Protection Act are steps in the right direction, as they are a first step in helping people retain their [digtial] sovereignty.

Moreover, when it comes to establishing computational laws I have little doubt that we'll start making progress, but it will take years for a meaningful impact to be felt from our efforts.

But all of the above is not enough.

What Actions Can We All Take?

Again, I agree with Tufekci's recommendations that establishing robust regulations and laws will help us get a handle on data inference practices; however, I don't think that these actions alone will solve the problem. It is important that each and every one of us learn to take actions into our own hands to protect and manage our data, our privacy.

What's privacy? I've adapted and extended Alan Westin's definition of privacy as follows,

Privacy is the ability for an individual or groups of individuals to determine for themselves when, how, for how long, for what purpose, for what intent, to what extent, and on what terms personal data about them [including identity attributes] is communicated and exchanged.

Adapted from Alan Westin's (1968) definition of privacy.

In other words, privacy is about maintaining authority over the flows of information. In order for us all to take authority over our information, I encourage each and every one of us to consider following the five-fold path to digital sovereignty.

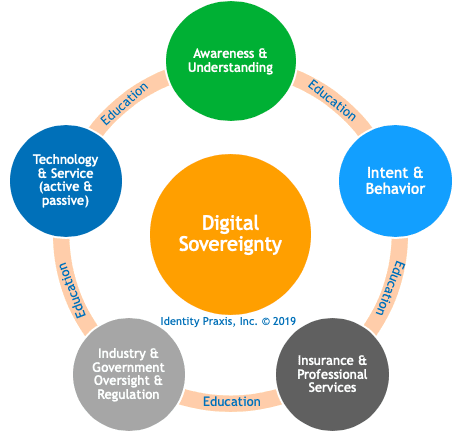

The five pillars along the five-fold path to digital sovereignty are,

- Awareness & understanding, we need to develop an awareness and understanding of the role our data plays throughout society and learn to optimize its value and mitigate the risks from its misuse.

- Intent & behavior, once we are aware and understand the role of our data, we need to consciously choose our intent and behavior, we need to decide what we will keep doing, stop doing, or do differently based on our awareness and understanding.

- Insurance & professional services, we need to mitigate risk and manage opportunity by taking on appropriate insurances and professional services to mitigate the impact of harms from data misuse and to optimize its upside.

- Industry and government oversight and regulation, as recommended by Tufekci, we need to influence and support the refinement and development of appropriate laws and regulations to maintain an industry equilibrium (The Identity Nexus), but we also need to enact our rights so that these laws and regulations remain intact and relevant.

- Technology & Services (Active & Passive), we need to adopt active (e.g. password manager, VPN, or personal data manager) and passive (e.g. adblocker, antivirus software, or darknet monitoring) technologies to both mitigate risks and protect and take advantage of opportunities.

An underlying element of all the pillars along the five-fold path to digital sovereignty is education. We need to be ever vigilant in managing our identity and personal information. We should not leave it to chance.

One good source of current privacy education is the New York Times Privacy Project. The team has and continues to publish valuable insights.

Being measured and scored in today's society is inevitable. What we chose to about it is our choice.

REFERENCES

Bajaj, K. (2017, April 11). Total worldwide data will swell to 163 zettabytes by 2025. The Economic Times. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/total-worldwide-data-will-swell-to-163-zettabytes-by-2025/articleshow/58118131.cms

Bradley, J., Loucks, J., Macaulay, J., & Noronha, A. (2013). Internet of Everything (IoE) Value Index How Much Value Are Private-Sector Firms Capturing from IoE in 2013? [White Paper]. Retrieved from Cisco website: https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/en_us/about/business-insights/docs/ioe-value-index-whitepaper.pdf

Dixon, P., & Gellman, R. (2014). The Scoring of America: How Secret Consumer Scores Threaten Your Privacy and Your Future (p. 1~89). Retrieved from World Privacy Forum website: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2014/08/00014-92369.pdf

2017 Identity Fraud Study, Javelin Strategy & Research

Pritchard, M. (2018, April 11). Procter & Gamble chief brand officer calls for new media supply chain. Retrieved April 12, 2019, from American Marketer website: https://www.americanmarketer.com/2019/04/11/procter-gamble-chief-brand-officer-calls-for-new-media-supply-chain/

Reinsel, D., Gantz, J., & Rydning, J. (2017). Data Age 2025: The Evolution of Data to Life-Critical Don’t Focus on Big Data; Focus on the Data That’s Big (pp. 1–25). Retrieved from IDC website: https://www.seagate.com/www-content/our-story/trends/files/Seagate-WP-DataAge2025-March-2017.pdf

Tufekci, Z. (2019, April 21). Think You’re Discreet Online? Think Again. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/21/opinion/computational-inference.html

Westin, A. F. (1968). Privacy and freedom. New York: Atheneum.

No Comments.